Why Test?

As a tennis player, it is OK to be strong. Agassi could bench press 315. We have personally witnessed Division I tennis players deep squat close to 300lbs at 1 m/s concentric. We have tested many tennis players at over 65 kilos in handgrip strength. We have seen tennis players perform 8 repetitions with 25lbs at 4010 tempo in the seated dumbbell external rotator exercise.

Imagine the strength levels required by the shoulder to prevent the arm from coming out of the socket during a 140mph serve?

Too often, young tennis players are pushed away from strength training and pulled toward speed, agility, and quickness drill training. This goes back to the old saying “you cannot fire a cannon from a canoe.” It’s like adding the icing before you make the cake?

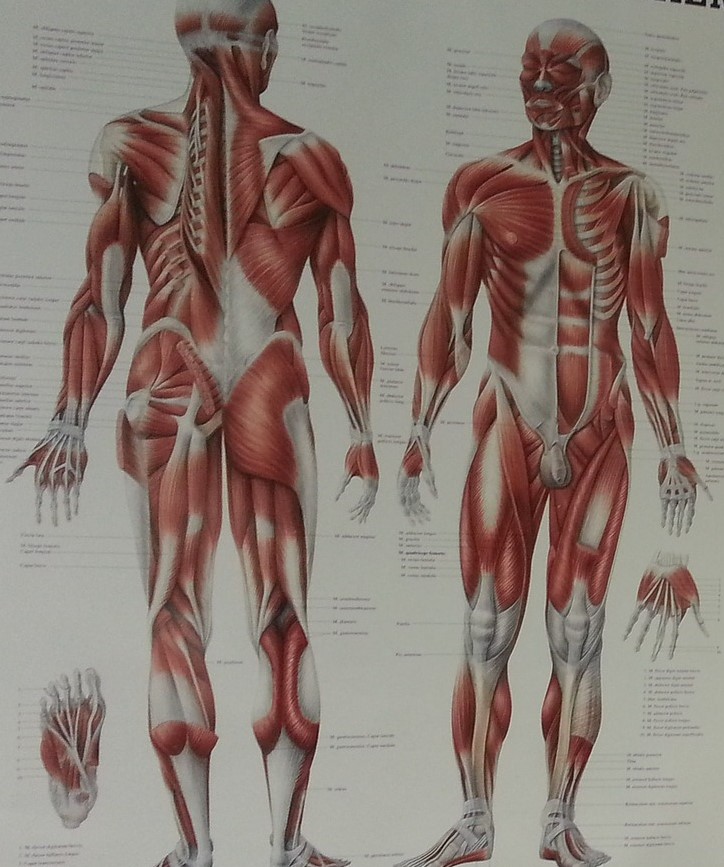

With its repetitive nature, muscular imbalances are not uncommon in tennis. The explosive mechanics of serving can lead to shoulder and elbow imbalances. Favoring the backhand or forehand can lead to the over-development of low and mid-back musculature on one side vs the other. To get technical, weakness in the extensor carpi radialis forearm muscle is commonly seen in those suffering from tennis elbow. In the 5-10-5 testing, athlete’s may get “stuck in the mud” when changing direction off one leg vs the other. If you are lucky enough to have access to some Hawkins Dynamics force plates, any discrepancy between right and left leg in jumping and landing mechanics/power can be seen.

Repetitive trauma can often be the culprit for many nagging injuries. When a movement pattern is repeated over and over again without proper strengthening of the antagonistic muscles, an overloading of those muscles and surrounding tissue may result. The overloading causes an imbalance between the antagonistic muscle groups.

Structural Balance

When driving by any building construction site, steel beams, re-bar, and concrete are all visible staples of the landscape. Each of these plays a vital role in the stability of the structural framework of a building. For example, if the placement or level of just one beam or re-bar is not precise, the stability of the entire framework becomes compromised. The musculoskeletal system of the human body is no different.

Understanding that for serious players, tennis is a year round sport, keeping the athlete “structurally balanced” is important. With practices nearly every day, consisting of dozens of strokes, serves, and volleys, the negative effects of pattern overload can eventually creep in after years of training.

Negative health consequences ranging from chronic pain to acute injury can result from these faults in one’s framework. According to a 2008 study out of the prestigious British Journal of Medicine, most ACL tears in adolescents and young adults occurred while participating in sports (4), with female athletes at a five-fold greater risk than their male counterparts (3).

The concept of structural balance is the brainchild of world-renowned strength coach Charles Poliquin. After training thousands of athletes at all levels of sports Olympic and Professional, coach Poliquin noticed trends between athletic performance and optimal strength ratios between agonist, antagonist, and synergistic muscle groups. Understanding that the body is only as strong as its weakest link, he understood these weak links must be addressed in order to reach athletic potential.

Oftentimes when extensive attention is paid to one muscle group at the expense of others, muscular imbalances may occur. The overworked muscle may become shortened while its antagonist becomes lengthened and weak. For example, the muscles you see when looking in a mirror, chest, abs, and biceps, often receive more training attention than their less visible counterparts, the external rotators, back, and triceps. An over-emphasis on these anterior muscles, in addition to a lack of proper training for their antagonists may lead to rounded forward shoulders, hunched forward posture, or constant elbow flexion, all of which can lead to an increased potential for injury.

Another common muscular imbalance, attributable to extended periods of sitting, is tight hip flexors and inhibited hip extensors. When a muscle becomes chronically shortened and overactive, in this case the hip flexors, the motor cortex part of the brain sends neuro-inhibitory signals to the antagonist telling it to relax or stand down. This phenomenon is referred to as reciprocal inhibition. With reciprocal inhibition, there may also be an over-reliance on the assistive, or synergistic, muscles, further exacerbating any structural imbalances.

To assess structural balance, specific strength-based exercises and movement screens are used to test for imbalances throughout the entire musculoskeletal chain. The movement screens assess lower body function and muscular balance, while the strength tests assess ratios between (X) upper body and lower body exercises. For example, optimal structural balance of the shoulder girdle is reflected by the ability to perform eight repetitions in the seated dumbbell external rotator exercise with roughly 10% of a trainee’s one repetition max in the flat barbell bench press.

If you are interested in learning more about Structural Balance, the Poliquin Group offers the PICP Level I Certification Course and Level 2 Certification course. Level I teaches upper body structural balance testing, fundamentals of program design, and more. Level 2 teaches Lower Body structural balance testing, exercise progressions, program design based off of upper and lower body structural balance testing, and more.

Here are two great resource articles on Charles Poliquin’s Structural Balance and Strength Ratios

1: Bigger, Faster, Stronger Structural Balance Article

2: Article written by Charles Poliquin for T-Nation

3: Upper and Lower Body Strength Ratios

As you can see, imbalances can increase the potential for injury. Sitting in the stands while milking an injury will not improve performance, nor will it help the tennis athlete climb in the rankings.

Sample Youth Tennis Player Muscular Balance Evaluation

Name___________________ Date__________

- Overhead Squat Evaluation:

| Pain | Depth | Left Knee | Right Knee | Weight Shift | Left Heel | Right Heel | Torso | Left Shoulder | Right Shoulder |

| Y | <90 | Valgus | Valgus | Left | Pron | Pron | Lean | Elevated | Elevated |

| N | >90 | Varus | Varus | Right | Int Rot | Int Rot | Rot | Fwd | Fwd |

2. Klatt Test

| L Pain | Left Knee | Left Foot | Hop/Stable | Torso | R Pain | Right Knee | Right Foot | Hop/Stable | Torso |

| Y | Valgus | Pron | L/R | Left | Y | Valgus | Pron | L/R | Left |

| N | Varus | Inv/Ev | Y/N | Right | N | Varus | Inv/Ev | Y/N | Right |

3. Single Leg Hamstring Curl (Kneeling, Prone, Standing, or Seated)

| Right Leg Natural | Right Leg Plantar Flexed | Left Leg Natural | Left Leg Plantar flexed |

| Lbs: | Lbs: | Lbs: | Lbs: |

| Reps: | Reps: | Reps: | Reps: |

4. Pushup Up Evaluation

| Shoulders | Hips | Low Back | Reps |

| Right: | Right: | Lordosis: | Pre-Rest/Technical Break: |

| Left: | Left: | Kyphosis: | Total: |

5. Chin Up Evaluation

| Shoulders Hang | Shoulders Pull | Elbow Flexors | Reps |

| Right: | Right: | Right: | Pre-Rest/Technical Break: |

| Left: | Left: | Left: | Total: |

6. Trunk Curl Up Evaluation

| No Anchor | Anchored |

| ROM %: | Reps: |

| Reps: |

7. Low Back Evaluations

| Visual Imb/Hyp | Lateral Plank | Palloff Press | Eyes Closed Weight Distribution |

| Thor: | Left: | Left: | Right/Left: |

| Lumbar: | Right: | Right: | Heels/Toes: |

8. Shoulder Evaluation

| Seated DB Ext Rot | Standing 1 Arm Trap-3 | Egoscue Shoulder Circles | Egoscue Elbow Touches |

| Right: | Right: | Reps: | Reps: |

| Left: | Left: | Weight Distribution: |

Other Evaluation Options

Egoscue Upright Posture Self-Evaluation

NASM (National Academy of Sport Medicine) Assessment

Stretch To Win Personal Flexibility Assessment

CHEK Institute Integrated Movement Science Assessment

Body Mechanic and Kinetic Chain Enhancement

Neurotransmitter Dominance Testing

Strength, Acceleration/Power, and Fitness Testing

Depending on the type of tennis player you are, the average point in tennis may take approximately 10 seconds or less. Whether you prefer serve and volley, baseline, or all court, the max distance covered per sprint or lateral movement is relatively short. Fast twitch explosive movements including serve, accelerating, lateral movement, decelerating, ground strokes and net play, dominate tennis. There is little, if any, slow twitch requirement.

Too often, athletes competing in explosive sports like tennis and volleyball, emphasize training of slow twitch muscle fibers and aerobic energy systems at the expense of their fast twitch and anaerobic energy systems. In other words, these athletes may be dampening the effectiveness of their fast twitch explosive capabilities while enhancing the slow twitch endurance capabilities. Short burst sprint ability versus slow pace marathon running capacity.

Each point in tennis requires acceleration, deceleration, speed, and agility. Each of these requires strength, stability, and power.

Btw, did you know that acceleration is trainable by roughly 30%?

Performance and Recovery Testing Tools

Hawkins Dynamics Force Plate Testing

The Young Tennis Player SAP Profile

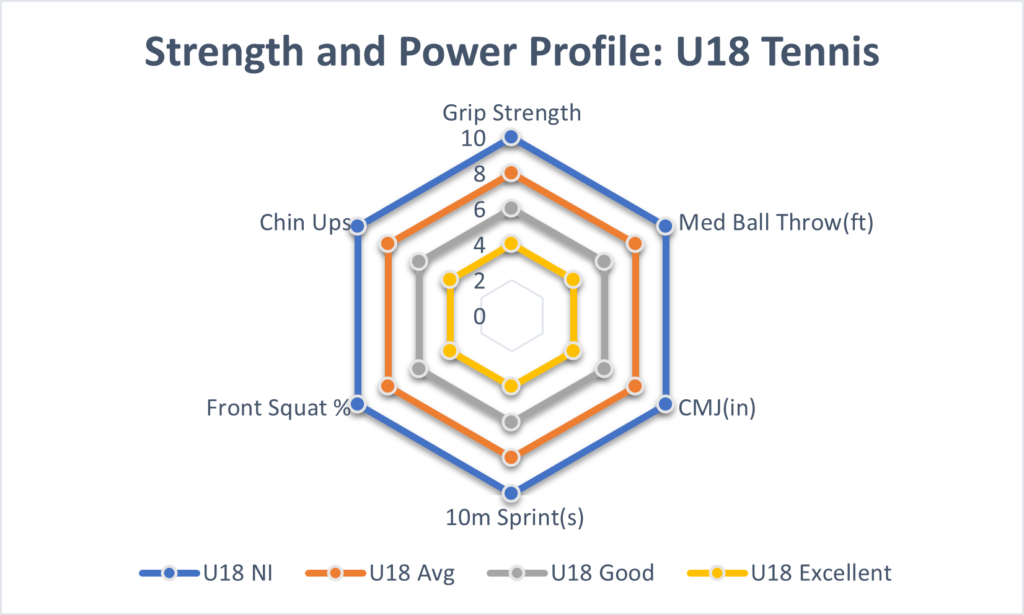

After evaluating structural/muscular balance and testing performance predictors, it’s time to create the athlete’s working profile.

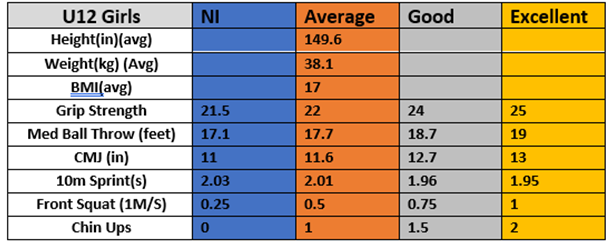

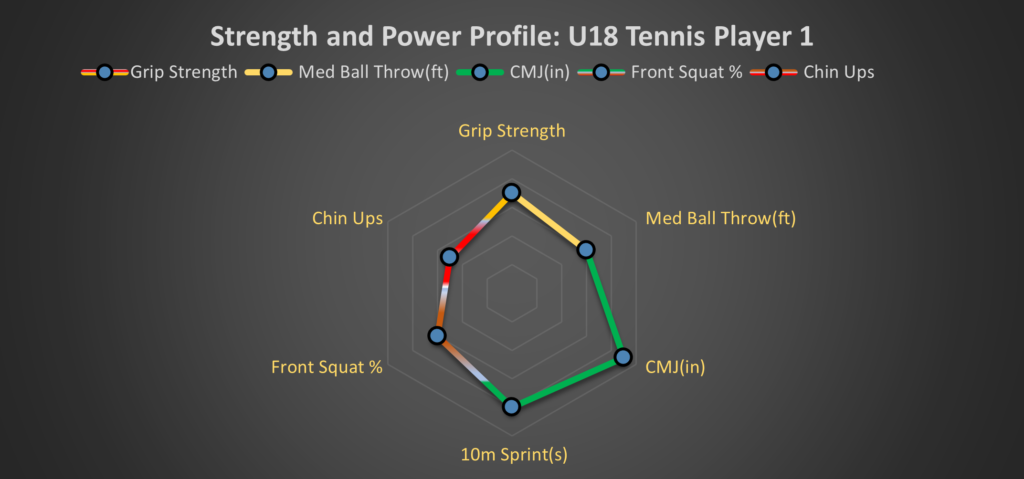

An excellent review from the British Journal of Sports Medicine analyzed the data of over 119 scientific studies to determine which physical tests were most effective for evaluating young tennis players (2). By combining these statistics (2) and with our own data from over 20 years of working with Nationally ranked, top New England, elite college, and high school/youth tennis players, we put together a working, organic SAP (Strength, Acceleration/Power) profile that continually guides the athletes training and recovery. (We’ll get into the training more in part 2 of this article series).

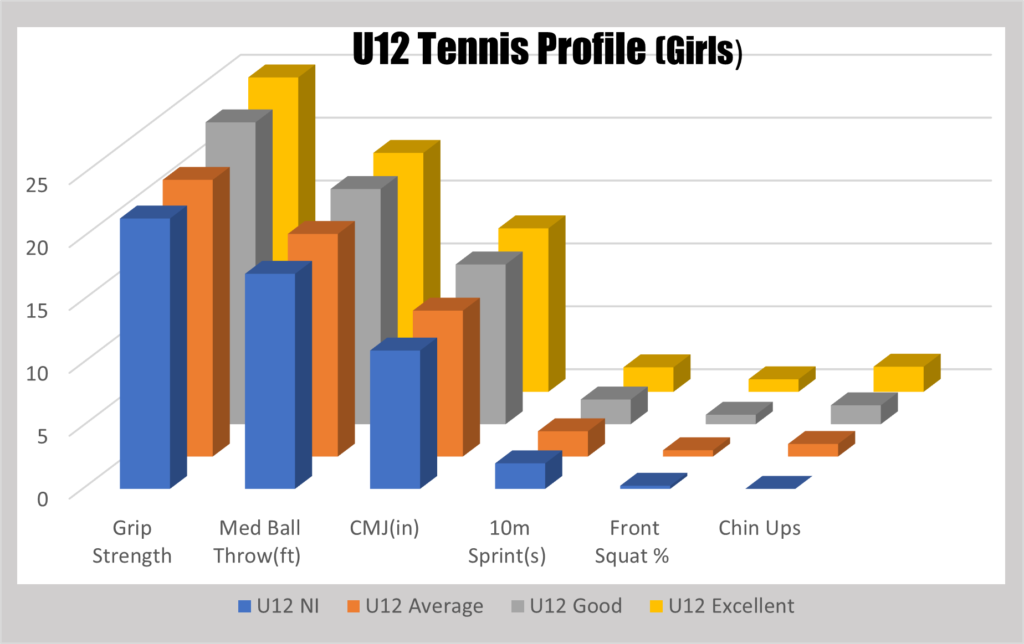

U12 Girls

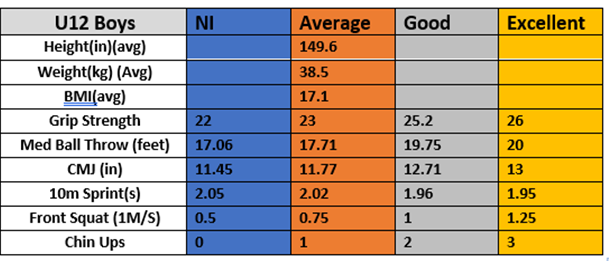

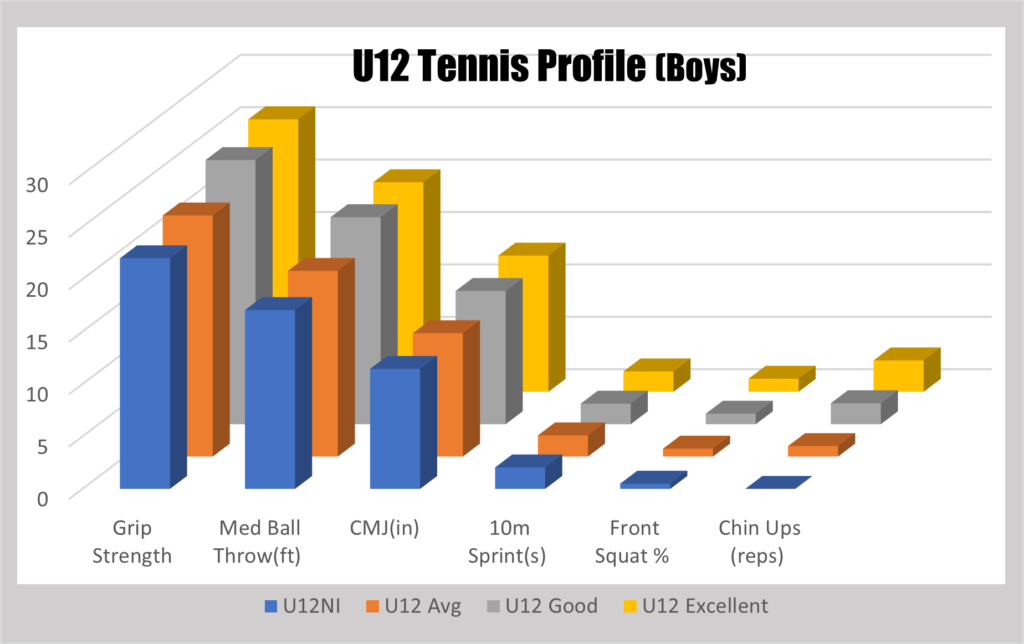

U12 Boys

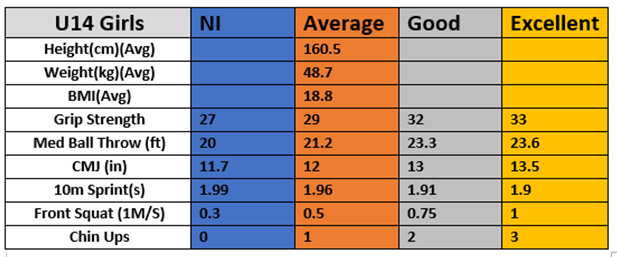

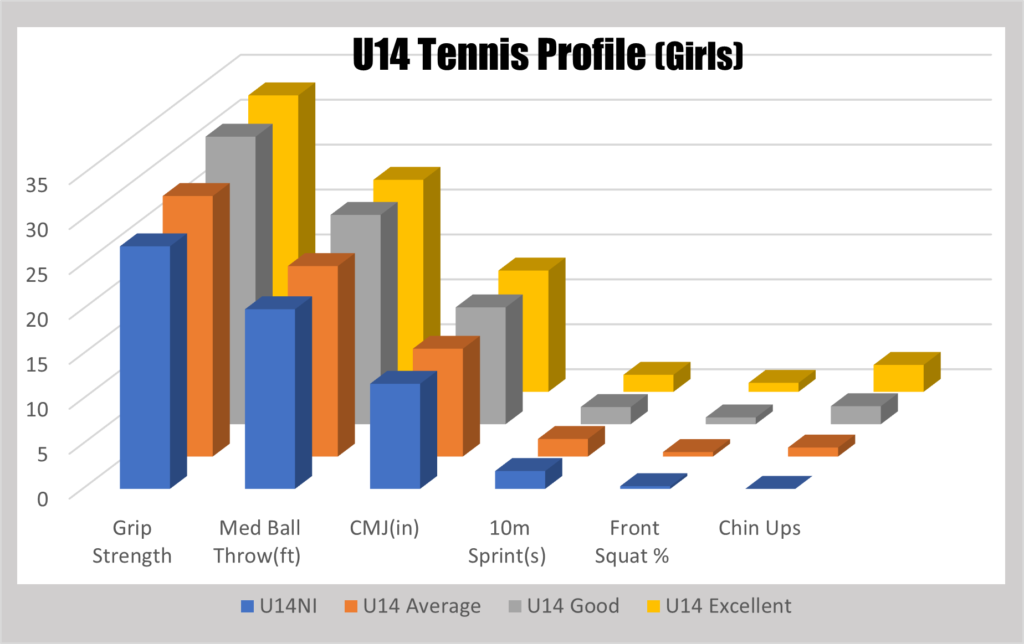

U14 Girls

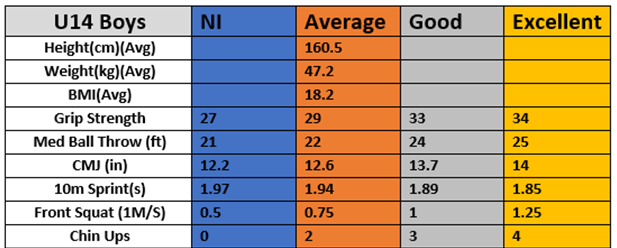

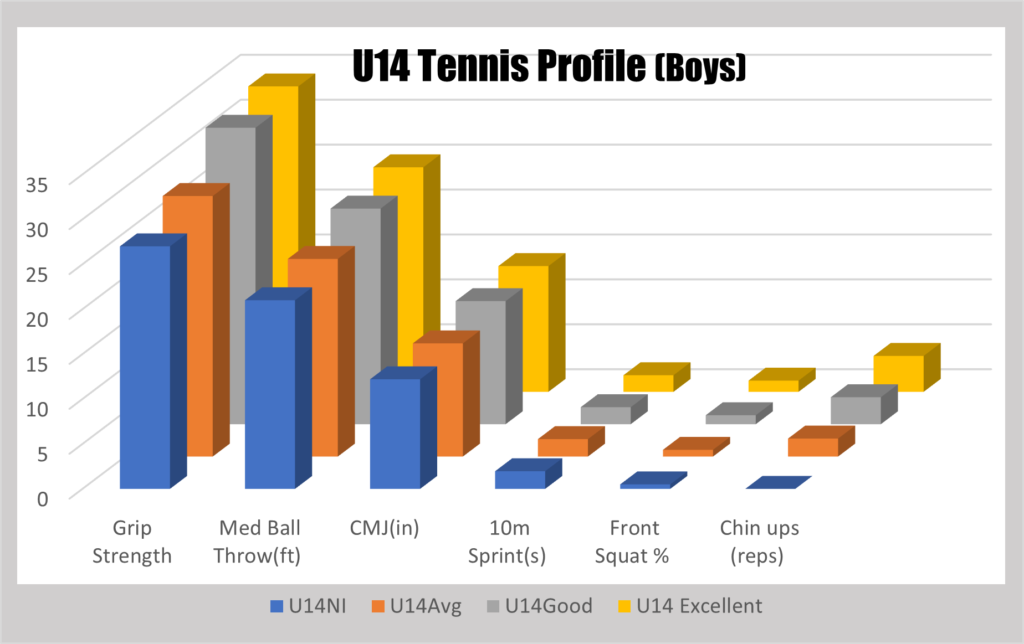

U14 Boys

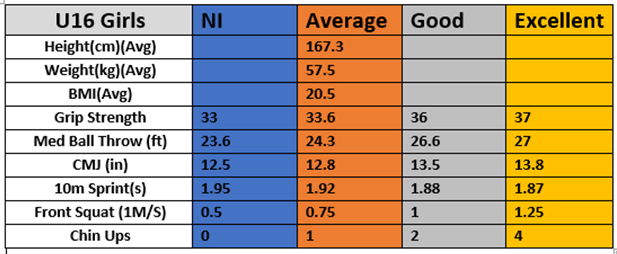

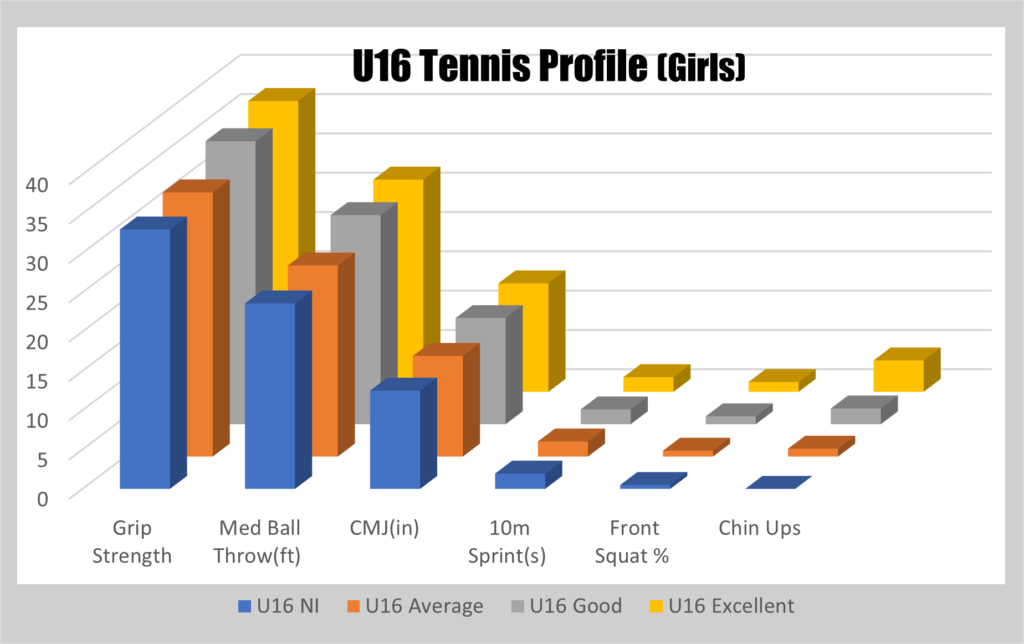

U16 Girls

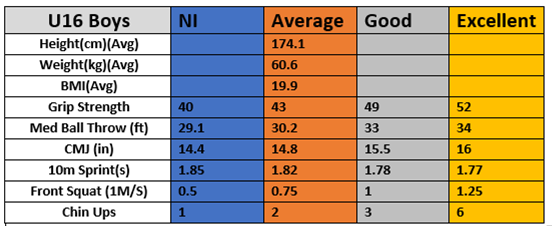

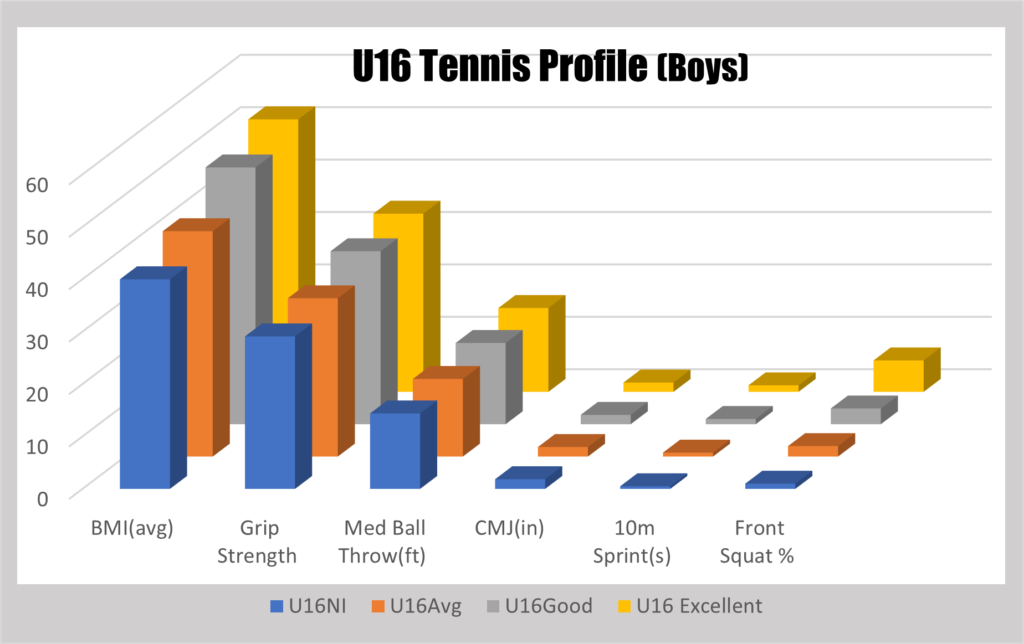

U16 Boys

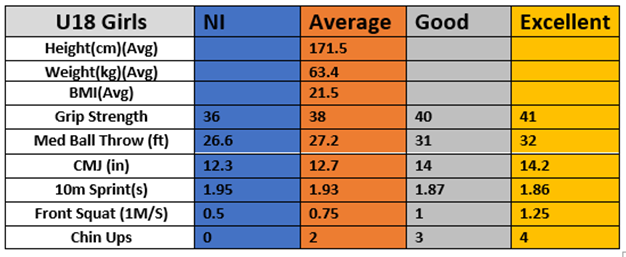

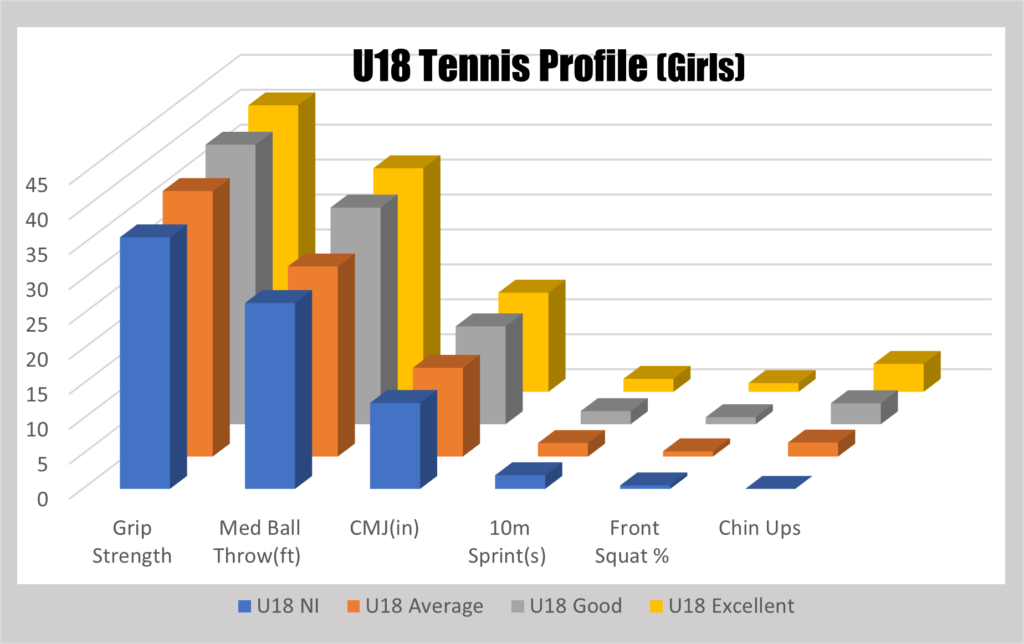

U18 Girls

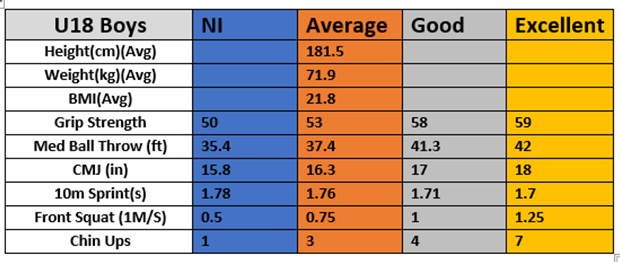

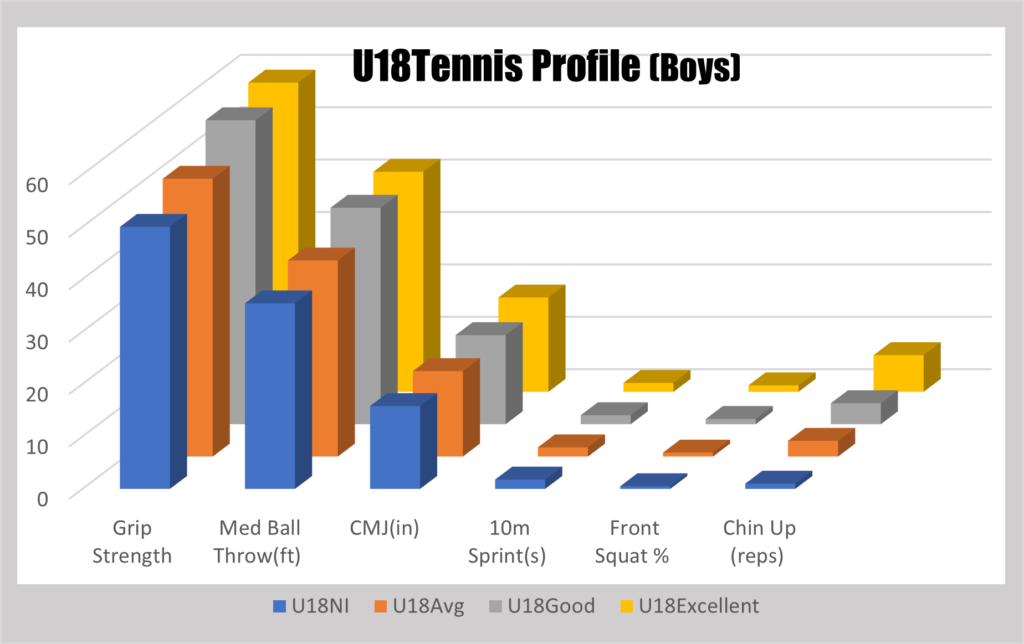

U18 Boys

Sample Individual Athlete Profile Template

Sample Working/Organic Athlete Profile

Sample Individual Athlete Strength and Power Profile

The evals and testing have been done. The sport, team, and individual athlete profiles have been created. Now what?

Time to analyze the profile and train. Stay tuned for Part 2 of The Ultimate Guide to Training for Young Tennis Players (2021).

Thx for reading!

If you are interested in learning more about increasing strength, acceleration, and explosive power, pick up a copy of our book Explosive Athlete today!

References

- Brown J, Wells G, Trotter A, Bonneau J, Ferris B. Back pain in a large Canadian police force. Spine. 23(7); Pp 821-827. 1998.

- Fernandez J et al. Fitness testing of tennis players: How valuable is it? British Journal of Sports Medicine. 48; Pp 22-31. 2014.

- Myer G, Ford K, Paterno M, Nick T, Hewett T. The effects of generalized joint laxity on risk of anterior cruciate ligament injury in young female athletes. American Journal of Sports Medicine. 36(6); Pp 1073-1080. 2008.

- Parkkari J, Pasanen K, Mattila V, Kannus P, Rimpela A. The risk for a cruciate ligament injury of the knee in adolescents and young adults: a population-based cohort study of 46,500 people with a 9 year follow-up. British Journal of Medicine. 42(6); Pp 422-426. 2008.